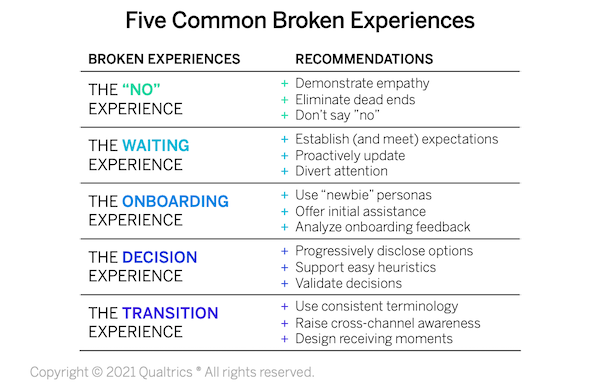

I’ve had the opportunity to work with 100s of organizations from just about every industry and every part of the world. While each situation is somewhat unique, there’s an abundance of commonalities. One area of consistency is in a set of experiences that are broken across many organizations. From retail to business-to-business, from London to Australia, from employee experience to customer experience, you’ll find these five significant opportunities for improvement:

- The “No” Experience

- The Waiting Experience

- The Onboarding Experience

- The Decision Experience

- The Transition Experience

The “No” Experience

The saying that the “customer is always right” is conceptually appealing but not always true. Sometimes customers (and employees) ask for unreasonable things (e.g., refund a plane ticket because a flight didn’t offer a snack, cut back to a two-day work week) or something that you can’t provide (e.g., deliver a product that is out of stock, private workspaces in an already crowded office). While you should always try to understand and address people’s needs, you can’t always say “yes.” Turning down requests is inevitable. These negative responses can be critical moments—especially if the request is for something important—so you need to handle them with care. Here’s how to design a “no” experience that will be less painful for those important stakeholders:

- Demonstrate empathy. Before turning down a customer or employee request, make sure that they feel like you understand them and are sympathetic about their situation. This becomes even more important in high-stress situations, like a request for a health insurer to cover a critical medical procedure. Train front-line employees and managers to acknowledge how people feel, reinforce that they are trying to help, remain calm, and never get defensive.

- Eliminate dead ends. Try not to leave customers without any options, as that will cause their negative emotions to escalate. If you can’t provide what they’re asking for, offer an alternative. For instance, if a customer wants a TV that isn’t in stock, suggest a similar model that can be shipped right away. Or provide details on an easy way to escalate their issue if they are still unhappy.

- Don’t say ”no.” It turns out that the words you use have a very real impact on how customers feel. A lighting manufacturer analyzed its call transcripts and found that calls with negative words like “can’t,” “won’t,” and “don’t” trigger negative customer reactions. The company’s satisfaction scores increased after training its representatives to use alternative phrasing.

The Waiting Experience

There’s an under-appreciated component of many customer journeys… waiting. Customers and employees end up waiting a lot. After hearing that they are eligible for a promotion… they wait. After hearing that a flight is delayed… they wait. After sending in an email complaint… they wait. During these “in between” periods, people’s anxiety can grow as they worry about what’s going on… even if it turns out that they have all of the available information. Here are some tips on how to improve the waiting experience:

- Establish (and meet) expectations. At every stage in a process, make sure to provide customers with a clear understanding about the substance and timing of the next step. This includes a clear timeframe about when they should expect an update. If a customer applies for a mortgage, then they should be given a definitive timetable, like, “We will contact you about any issues with your application within the next two days, otherwise you will hear about the mortgage approval within seven days.” And don’t leave customers on hold with your contact center for any extended timeframe without letting them know what to expect. Of course, none of this matters unless you actually do what you say you’re going to do.

- Proactively update. Whenever customers have an extended waiting period, assume that they will wonder if the status of their situation has changed…. even if you don’t believe that they have any reason to think that way. Plan to provide updates, even if nothing is new. Rather than waiting for a change in status to trigger an update to passengers about a delayed flight, JetBlue staff doesn’t let too much time go by without providing announcements to keep passengers up to date. Sometimes just letting customers know that “we’re still on track” or “nothing has changed” is a valuable communication.

- Divert attention. It turns out that people don’t really remember time. Instead, they remember how they felt about the time they spent. So even if you can’t reduce waiting time, you can still change how people remember the experience. If your customers are waiting in a space you control, like a check-out line or a phone call queue, think about keeping their minds occupied so that they don’t focus on the time. Useful updates on a call queue or engaging content on a video screen can help make the wait time seem shorter.

The Onboarding Experience

I often say, “New customers want to love you, but they’re willing to hate you.” New customers are anxious to get value from your organization, but they can also get easily frustrated. This is also true with new employees and new partners. Their lack of context about your products, processes, procedures, and nomenclature can make it difficult for them to navigate interactions with your business. At the same time, your organization lacks any stored-up goodwill with new people, which makes it harder for them to overlook problems. So you can’t treat these “beginners” the same way you treat more tenured people. Here are some ideas for improving the onboarding experience:

- Use “newbie” personas. Human beings are naturally self-centered —we look at the world through our own eyes. This presents a significant challenge since the people making decisions about experiences often know so much more about the domain than new customers or employees do. That’s why it’s useful to craft design personas that are specifically focused on new customers. Think about making “newbie” variations of existing personas to identify what they do and don’t know. These should be used as the primary personas for designing all onboarding experiences and to check that other experiences can be easily navigated.

- Offer initial assistance. No matter how well you’ve designed the onboarding experience, you should expect that some new people will run into problems. So you should proactively provide additional support, whether it’s robust in-product help content (created with a “newbie” in mind) or a way to reach a live person when they run into a problem. Even if you aren’t able to offer high levels of human support for all customers across their lifecycle, consider investing in these additional resources for customers during the critical onboarding stage.

- Analyze onboarding feedback. Since new customers and employees view experiences differently than more tenured ones, it’s important to examine their feedback separately so it doesn’t get muted. Consider creating specific experience metrics around these new people and, if you have the data, independently look at their underlying drivers of success. It’s also valuable to segment the comments from these newbies as well. If you have a good text analytics platform, then you can analyze the data for sentiment and themes. Otherwise, just read a healthy dose of their open-ended responses.

The Decision Experience

How much of a deductible? Do you want to lease or buy? Relaxed, regular, or slim fit? We ask people to make all sorts of decisions that they may or may not be prepared to make. In some cases, they don’t have the requisite knowledge to understand their choices, or they just don’t want to devote a lot of time thinking about it. In other cases, people relish the process of researching their options. In all cases, however, people can have buyer’s remorse (see this great TED Talk by Barry Schwartz, Paradox of Choice). So it’s critical to think about who’s making the decision, what options they’re presented with, what help they need to choose, and how they feel after making the decision. Here are some tips for improving the decision experience:

- Progressively disclose options. While it’s tempting to provide as many options as you can to people, this can overwhelm people and create “analysis paralysis.” Rather than showcasing everything at once, consider highlighting a few “popular” options, with short, helpful descriptions, and then allowing people to look at others if they want. This will help them to either pick one of the initial offerings or orient them around the differences across options.

- Support easy heuristics. Make it easy for people to make a quick, smart decision. Social tags like “most popular” or “highest rated” help shortcut the process in situations where people don’t want to actively research their options. In more complex situations, consider providing comparison tables that highlight a handful of the key criteria. This allows people to scan their options, and potentially lock into a criteria that they may see as the “tie-breaker.” Whatever you do, avoid forcing people to read through a lot of detail to learn about each individual option.

- Validate decisions. After someone makes a decision, they often fall into a period of doubt.. What did I just do? Did I make the right choice? Am I going to regret it? Try not to let that happen. Instead, immediately confirm their decision and reinforce that they made the right choice, both in their selection and in picking your organization in the first place. For example, you could tell them that they’ve selected one of the most popular options, that you’re sure they’ll enjoy it, and that you look forward to having them as a new customer.

The Transition Experience

It would be great if people could accomplish their goals within a single, simple interaction. Unfortunately, that’s not the norm. Most activities take multiple interactions that cross over multiple channels. A person may research some options online, talk to a colleague, visit a store to look at something, and then reach out to a contact center. It’s often easy to get lost in this process as the transition between modes leaves people feeling like they’re always starting from scratch. Here’s some advice for designing a better transition experience:

- Use consistent terminology. One of the key ways that people feel comfortable across transitions is if the different experiences share some common structural language. If a health plan’s website describes “quotes,” “claims,” and “customer service,” then it would be good for the IVR and customer communications to use those same exact words. It can be confusing, for instance, for the site to say “customer service” and the IVR to say “support”… and mean the same thing.

- Raise cross-channel awareness. When someone sees a product in a store and wants to purchase it online, they shouldn’t have to wonder if they’ve found the right thing. Provide a way to easily start the process when they are standing in front of the item, maybe by offering QR codes. Also, when someone calls the contact center during a website experience, consider providing a specific phone number or code so the rep has information about the previous experience.

- Design receiving moments. While every part of an experience can be important, the key area to focus on during a transition is the start of the second part of the transition…the receiving experience. It’s the point where people have a heightened sense of concern as they wonder what’s in store for them after spending time on their previous journey. If a customer calls into a contact center and the issue needs to be escalated to another agent, then the key moment is the point when the second agent initiates the conversation. Consider putting your best agents on those calls and actively design and test options to uncover best practices.

The bottom line: Now that you know about these broken experiences, please fix them.

Bruce Temkin, XMP, CCXP, is the Head of Qualtrics XM Institute