Survey Methodology

Experiences are in the eye of the beholder. This means that before an organization can meaningfully improve the quality of the experiences it delivers, it first needs to understand how people – including customers and employees – perceive their interactions with the company. Organizations traditionally capture this experience data (X-data) through surveys. However, any X-data generated by a survey is only as good as the survey itself. If the survey is poorly written or conceived, it’s not going to produce useful or accurate insights.

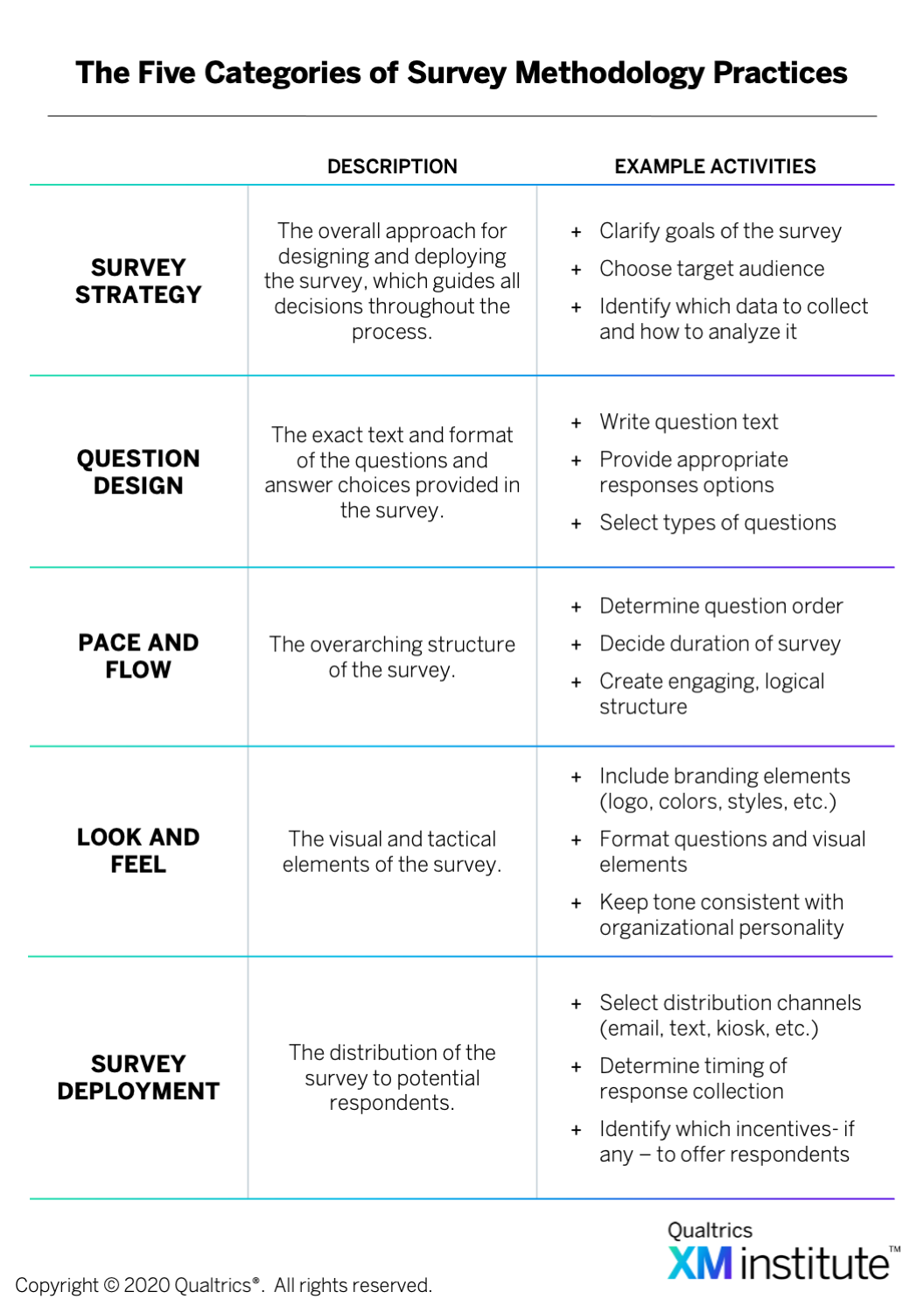

Fortunately, the field of survey methodology is a well-established academic discipline with an extensive body of literature, common tools and techniques, and defined best practices. Less fortunately, however, this knowledge has not yet permeated many organizations, and the people responsible for building and deploying surveys are often unfamiliar with survey methodology best practices. So to help practitioners create surveys that yield valid X-data, XM Institute has identified five categories of survey methodology practices that they need to focus on whenever they’re developing a survey  :

:

- Survey Strategy. Before you can create an effective survey, you must first identify and define a clear survey strategy. This strategy should serve as a North Star, guiding and aligning all the decisions you make as you move through the process. This category includes activities like defining the objective of the survey, selecting the target audience, identifying which data to collect, and determining how to derive insights from survey results.

- Question Design. The central features of any survey are the questions asked and the responses provided. If the questions are confusing or vague, if the answer choices are incomplete or unclear, then the results of the survey won’t actually reflect the opinions of respondents, rendering any data you generate meaningless. This category, therefore, encompasses all activities related to providing appropriate question text and response options.

- Pace and Flow. People are better able to understand and internalize information that’s presented within a clear narrative structure. So rather than ask respondents a string of random, disconnected questions, surveys should follow a logical flow, with smooth transitions between questions and a pace that keeps respondents engaged until the end. This category focuses on the overarching structure of a survey and involves all activities that pertain to the timing and thematic organization of its questions.

- Look and Feel. Because taking a survey is part of someone’s experience with your organization, the survey itself needs to properly represent your brand. If the tone and appearance of the survey do not match the rest of your organizational personality, respondents will find the experience jarring and may question the authenticity of your brand. This category covers the visual and tactical elements of a survey, everything respondents will see as they navigate through the questions.

- Survey Deployment. Once you have finished writing and designing the survey, you then need to get it into the hands of respondents. This category encompasses all activities and decisions associated with distributing the survey, such as the invitation language you use, when you send the survey, what incentives you offer, and how you nudge respondents.

Best Practices For Question Design

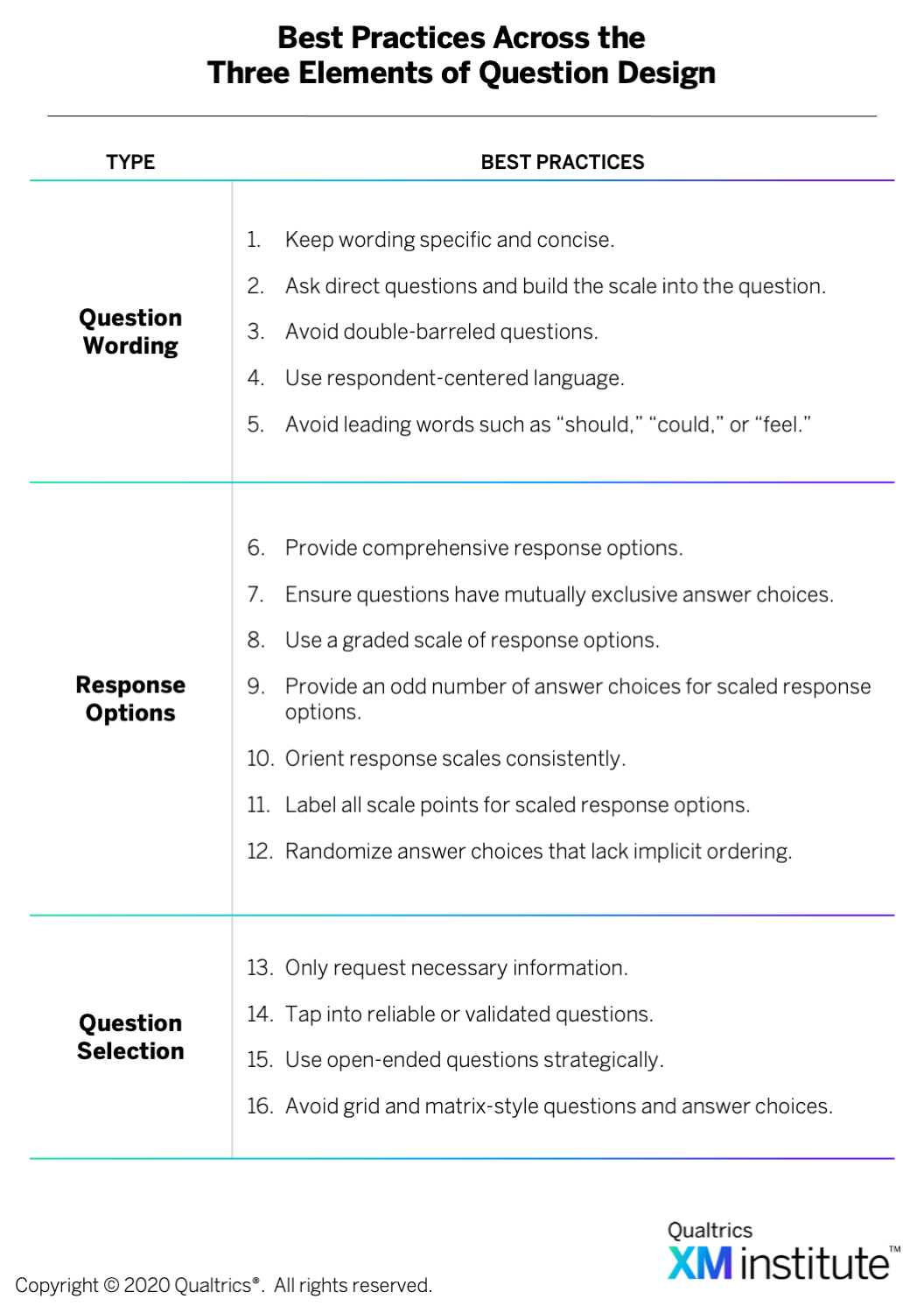

While all five of the categories of survey methodology are important, this report focuses exclusively on best practices within the category of Question Design. To understand how organizations can write surveys that are both informative for the business and engaging for respondents, we consulted with survey methodology experts across Qualtrics.1 Based on this research, we have identified the three elements of Question Design any practitioner should focus on to create effective surveys  :

:

- Question Wording. This component concerns the specific wording and phrasing of survey questions.

- Response Options. This component covers the way respondents can answer survey questions.

- Question Selection. This component encompasses how and when to use certain types of questions.

Question Wording

Well-written survey questions are the foundation of any successful survey. You need to communicate information and phrase questions in a way that is easy for all participants to understand and respond to. If your question text is ambiguous, biased, or poorly written, your survey won’t end up generating accurate and meaningful insights. To help you write effective survey questions, we recommend that you  :

:

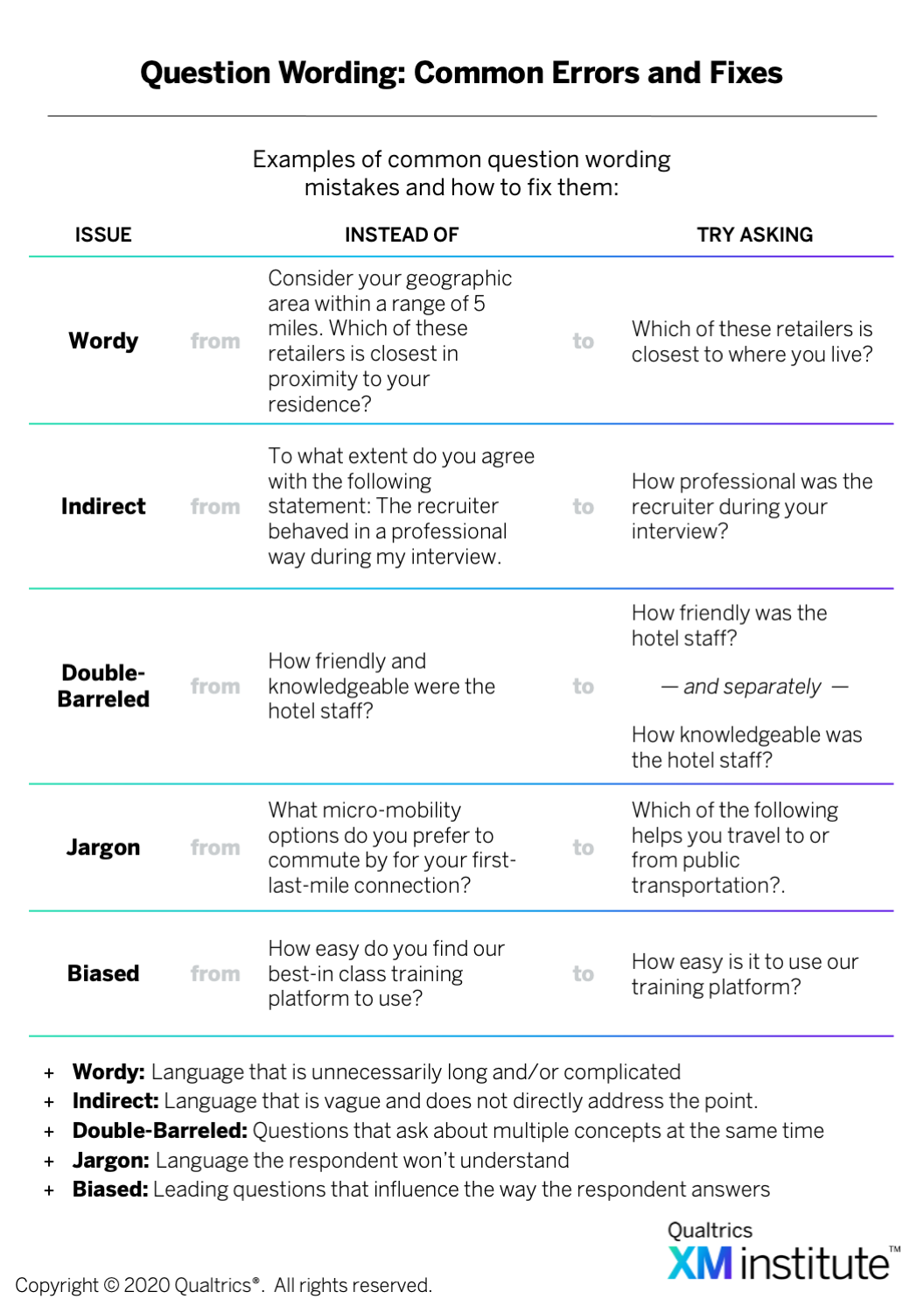

- Keep wording specific and concise. Respondents can’t provide accurate answers if they don’t properly understand what you’re asking. To ensure that your questions are easily understood and interpreted the same by all respondents, use precise, clear language that communicates your intent in as few words as possible. One way to accomplish this is by limiting the use of adverbs and adjectives. This will not only ensure that respondents understand your query, but it will also contribute to the validity of your data. For example, if you are trying to investigate the support for a particular candidate, you should phrase the question as, “How likely are you to vote for John Doe?” rather than, “Do you think it is likely that you will vote for the upstart candidate John Doe in the upcoming election?”

- Ask direct questions and build the scale into the question. In addition to being specific and concise, questions need to be direct, asking about an explicit situation rather than a general tendency. Wording that is vague or beats around the bush will lead to respondent confusion, misinterpretation of the question, and ultimately, unreliable data. By building the response scale into the question, you prevent this from happening. For example, if you’re looking to understand if you met a customer’s service expectations, ask, “How much did the quality of the service you received meet your expectations?” rather than, “To what degree do you agree with the following statement: ‘I was satisfied with the quality of service I received?’” The former option puts the scale – expectations – directly into the question while the latter does not.

- Avoid double-barreled questions. One common survey mistake is asking double-barreled, or even triple-barreled, questions. This type of question appears to ask about one concept but actually asks about two, often by connecting them with an “and.” For instance, asking customers, “How satisfied are you with the agent’s knowledge and friendliness?” or asking employees, “How connected do you feel to our company’s mission and culture?” Because these questions ask respondents to evaluate two separate concepts within a single answer, if respondents feel differently about each concept, it is impossible for them to accurately answer the question. It’s also impossible for you to know which of the concepts they are evaluating. Therefore, to ensure actionable results, separate distinct concepts into different questions. So in the employee example above, instead of asking about mission and culture, ask employees, “How connected do you feel to our company’s mission?” Then, separately ask, “How connected do you feel to our company’s culture?”

- Use respondent-centered language. The people taking your survey will have varying degrees of familiarity with your products, organization, and industry. So to make sure that respondents can quickly and accurately understand the questions, write to the least-informed respondent. This means avoiding technical, industry-specific jargon, acronyms, and grandiose or esoteric language. For example, if you are writing a survey for a bank, you likely want to avoid language like FinTech, operating subsidiary, account holder, and POS that will not be understood by all your respondents.

- Avoid leading words such as “should,” “could,” or “feel.” While on the surface they may not appear to change a question’s meaning, leading words such as “should” or “could” can introduce bias into a question. This bias, though subtle, may influence the way respondents answer, thereby compromising the validity of your data. So, for instance, rather than ask, “Should the United States adopt ranked-choice voting in Presidential elections?” rephrase the question to, “How much do you support using ranked-choice voting for Presidential elections in the United States?”

Response Options

The data you collect from a survey ultimately comes from how people answer the questions you ask. This means that to generate good data, you need to provide good response options. If these options are incomplete, confusing, poorly labeled, or haphazardly organized, you’ll end up with answers that don’t reflect people’s actual opinions, leading to less meaningful insights. To help you ensure you have the best response options for each question, we recommend that you:

- Provide comprehensive response options. It doesn’t matter how articulate your survey question is if the respondent isn’t able to answer it accurately because their preferred response option isn’t available. To increase the validity and reliability of your collected data, make sure you account for all the different ways a respondent may want to answer the question. One way to accomplish this is to include a “Not applicable,” “None of the above,” and/or “Other (please specify)” answer choice.

- Ensure questions have mutually exclusive answer choices. If respondents struggle to distinguish between different answer choices, they won’t be able to provide accurate responses. Avoid ambiguity by making response options mutually exclusive with one another. For example, if you are asking people their age, don’t provide answers like, “18-25,” “25-35,” 35-45,” etc. Respondents who are 25 or 35 won’t know how to correctly answer the question. These types of options, which offer either too many or no correct answer choices, will result in respondent frustration and confusion and, ultimately, compromised survey results.

- Use a graded scale of response options. If you ask people whether or not they agree with a particular statement, they’re likely to say they do – a phenomenon known as “acquiescence bias.” They are also likely to choose the affirmative response option when presented with only two answer choices. To overcome this natural inclination, write out full scales across the answer choices. So, for example, instead of providing binary “yes/no” or “likely/unlikely” answer choices, use a scale that allows for varying degrees of likelihood, such as, “Not at all likely,” “Not likely,” “Somewhat likely,” “Likely,” and “Very likely.” This will provide more valid data and allow you to analyze your results more deeply.

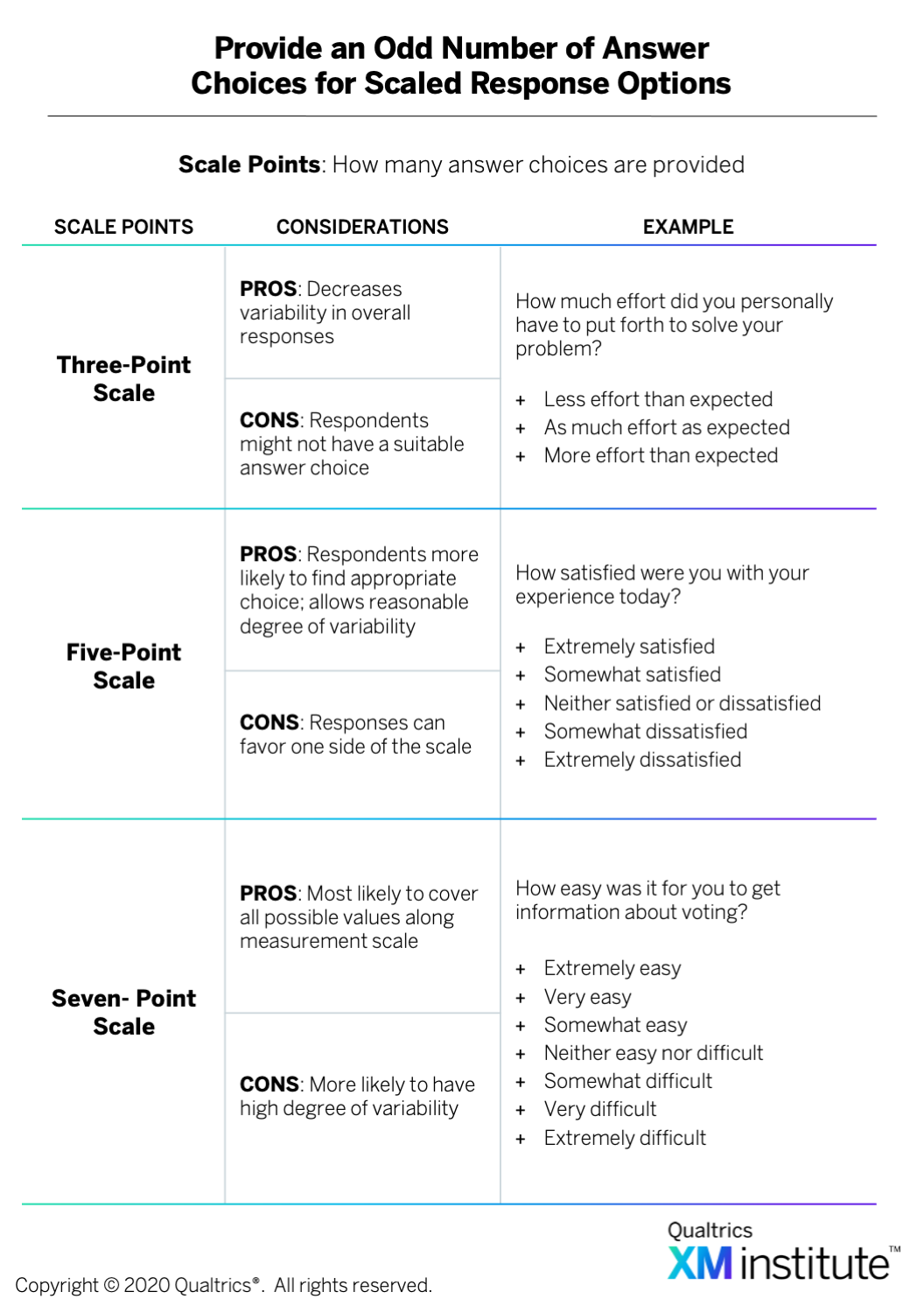

- Provide an odd number of answer choices for scaled response options. When scales have an even number of response options, there’s no neutral midpoint to balance the spectrum. This often leads to respondent confusion and a bias towards one end of the scale or the other, causing them to give an answer that may not accurately reflect their opinion. An odd number of responses, on the other hand, provides a balanced scale with a neutral option, allowing you to cover the entire range of potential answers. So when you’re creating a question with scaled response options, give respondents three, five, or seven answer choices

. For example, if you’re asking employees how likely they are to look for a new job, you could use a five- or seven-point scale with response options ranging from, “Very unlikely,” to “Very likely,” with a neutral midpoint of “Neither likely nor unlikely.”

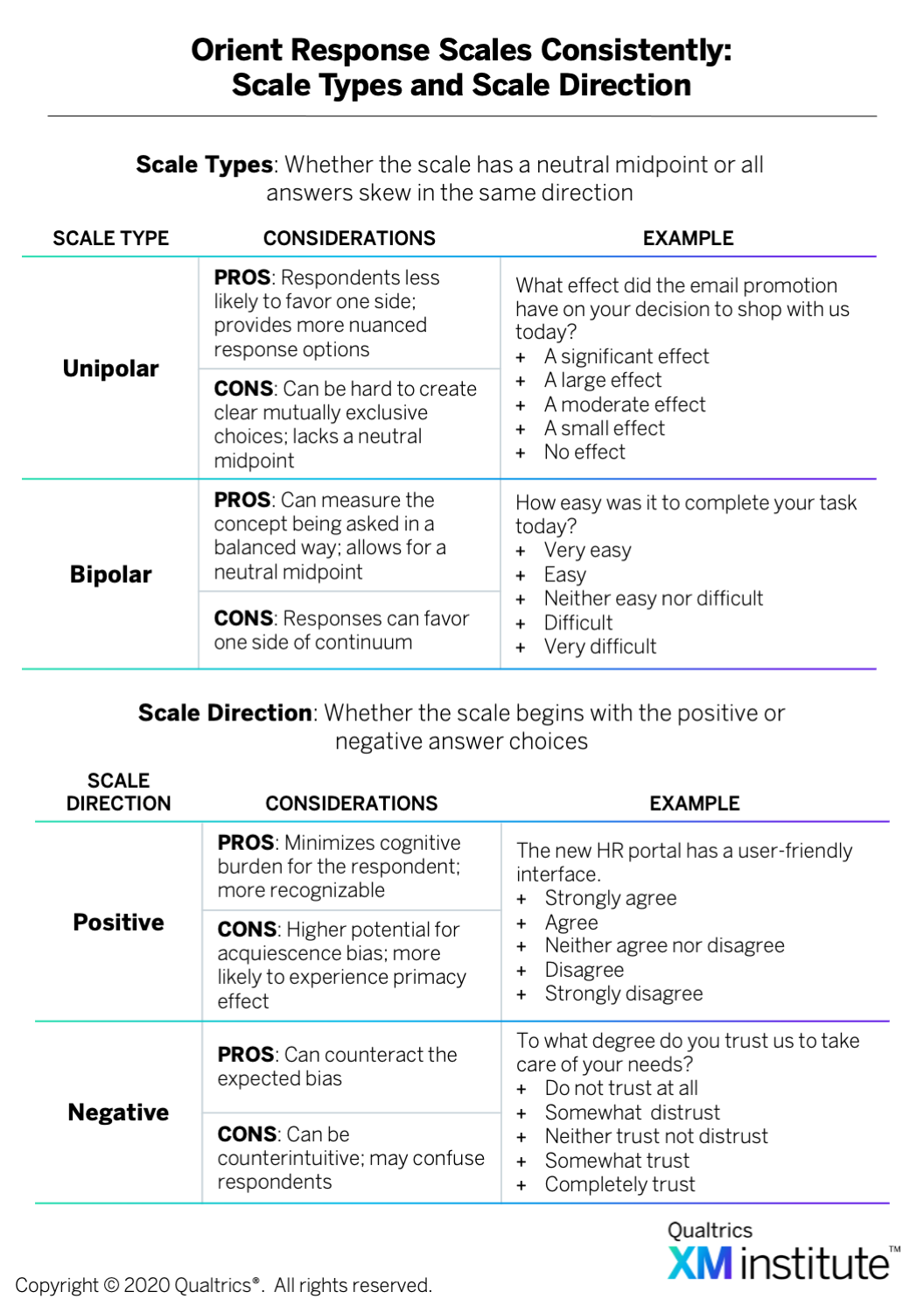

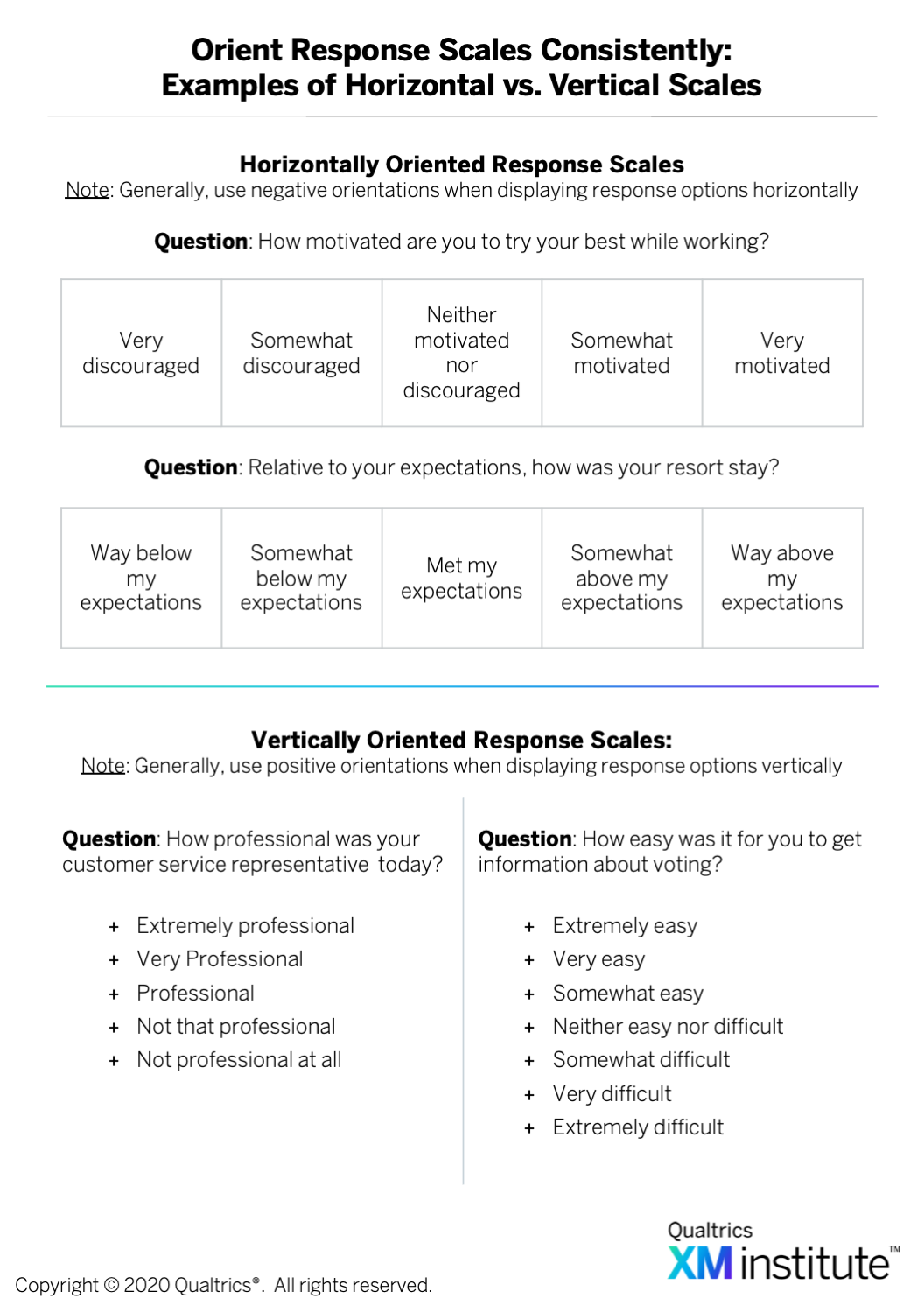

. For example, if you’re asking employees how likely they are to look for a new job, you could use a five- or seven-point scale with response options ranging from, “Very unlikely,” to “Very likely,” with a neutral midpoint of “Neither likely nor unlikely.” - Orient response scales consistently. Response scales can be oriented in a number of different ways. They can be either unipolar – meaning the answer choices all move in the same direction – or bipolar – meaning the scale has a neutral midpoint with positive answer choices on one side and negative ones on the other

. They can also be either positively or negatively oriented, which indicates which side of the scale is listed first. In positively oriented scales, statements in the affirmative – like those indicating agreement, satisfaction, positive emotions, or high likelihood – come first, while in negatively oriented scales, statements of dissent or unfavorable feelings – such as disagreement, dissatisfaction, or unwillingness to do something – appear first. Scales can also be displayed horizontally or vertically

. They can also be either positively or negatively oriented, which indicates which side of the scale is listed first. In positively oriented scales, statements in the affirmative – like those indicating agreement, satisfaction, positive emotions, or high likelihood – come first, while in negatively oriented scales, statements of dissent or unfavorable feelings – such as disagreement, dissatisfaction, or unwillingness to do something – appear first. Scales can also be displayed horizontally or vertically  . Which orientation you select will depend on your goal for the question. For example, positively oriented scales are easier for respondents to cognitively process, but negatively oriented scales can help counteract expected bias. Regardless of which orientation you choose, it is essential to keep the orientation consistent across all your survey questions.

. Which orientation you select will depend on your goal for the question. For example, positively oriented scales are easier for respondents to cognitively process, but negatively oriented scales can help counteract expected bias. Regardless of which orientation you choose, it is essential to keep the orientation consistent across all your survey questions. - Label all scale points for scaled response options. Make it easy for respondents to select the answer that best reflects their viewpoint by labeling each scale point in the response options. These labels should be easy to interpret, equally understood by all respondents, and cover the entire range of the response scale. It is also better to use words to describe these scale points rather than numbers. So for example, questions about satisfaction usually use the following scale: “Very dissatisfied,” “Somewhat dissatisfied,” “Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied,” “Somewhat satisfied,” and, “Very satisfied.”

- Randomize answer choices that lack implicit ordering. When an answer choice appears first, it will be selected more often than when it is listed second or third. To reduce this primacy effect, randomize the order that response options appear in. Shuffling answer choices for each respondent randomizes any bias that might be present and helps prevent an over-representation of one particular answer. So, if you were trying to identify which communication channels customers find most useful, you could provide a list of potential options – such as email, text, social media, etc. – and randomize the order in which these choices appeared for each respondent.

Question Selection

In addition to determining how to phrase questions and which answer choices to provide, practitioners also need to make some behind-the-scenes decisions when selecting which questions to ask. While respondents may not be as aware of these decisions, they nevertheless affect both the quality of the experience and the validity of the data. They also make it more efficient for you as a practitioner to build the survey. To determine which questions you should include, we recommend that you:

- Only request necessary information. While surveys may provide valuable information to organizations, for respondents, the process of filling them out is rarely enjoyable or rewarding. So to make the survey easier – and less annoying – for people to complete, don’t ask them for information you already possess and only include questions that directly contribute to the purpose of the survey. For example, if you distributed the survey via email, don’t ask for a respondent’s email address. If you’re not going to include demographic information in your survey analysis, don’t ask respondents for their age or gender. Avoiding these types of unnecessary questions will save the respondent time and energy and consequently increase the overall quality of the data you collect.

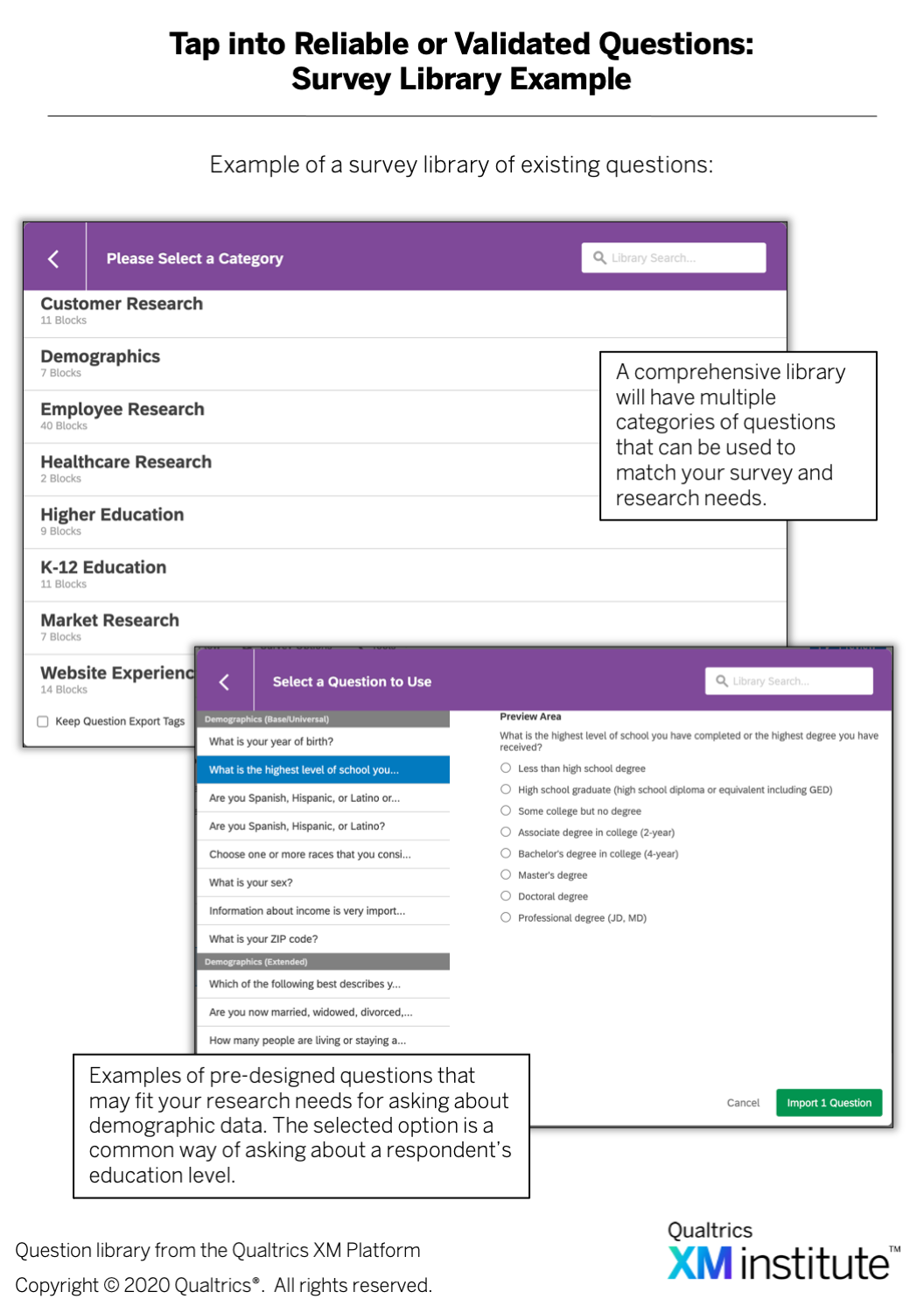

- Tap into reliable or validated questions. Survey methodology is a well-established academic discipline. Rather than reinventing the wheel each time you write a survey, tap into existing, research-backed ways of measuring the concept you’re investigating

. These pre-designed questions not only have a proven track record of capturing reliable and consistent data, but – because they are standard across organizations – using them will allow you to compare your results to those of other companies or industries. Additionally, because they are common survey questions, respondents are more likely to recognize and understand them, resulting in a smoother survey experience. For example, if you’re looking to measure customers’ likelihood to recommend, it makes sense to use the popular 11-point Net Promoter®️ Score (NPS®️) question.2 Other examples include common methods of asking for demographic information and typical phrasing for customer or employee satisfaction questions.

. These pre-designed questions not only have a proven track record of capturing reliable and consistent data, but – because they are standard across organizations – using them will allow you to compare your results to those of other companies or industries. Additionally, because they are common survey questions, respondents are more likely to recognize and understand them, resulting in a smoother survey experience. For example, if you’re looking to measure customers’ likelihood to recommend, it makes sense to use the popular 11-point Net Promoter®️ Score (NPS®️) question.2 Other examples include common methods of asking for demographic information and typical phrasing for customer or employee satisfaction questions. - Use open-ended questions strategically. Because open-ended questions are time-consuming and burdensome for the respondent, use them judiciously and at the end of the survey where possible. While you may want to collect open-ended feedback to dig deeper into a particular response or experience, it’s best to limit the number of times you ask open-ended questions. We recommend not using them for more than 10% of your survey questions. However, there are certain instances where open-ended text questions can actually decrease survey duration and minimize fatigue, such as allowing respondents to manually enter their age rather than forcing them to scroll through a drop-down list. In those cases, using open-ended questions will actually improve the survey experience.

- Avoid grid and matrix-style questions and answer choices. Using matrix-style questions makes it more likely that respondents will participate in straight-lining – the process of choosing all the answer choices in the same or similar columns just to get the survey done faster. To prevent this behavior, ask each question as its own distinct element or opt for separate pages, even if the wording and its accompanying response options are similar to other questions. If, for example, you are asking employees to evaluate their level of satisfaction with different journeys in their employee experience – such as onboarding, professional development, and the promotion process – you should ask about each journey separately, even though the response options are identical.

- The following research experts at Qualtrics contributed to this research: Emily Geison, Benjamin Granger, Carol Haney, and Luke Williams.

- Net Promoter Score, Net Promoter, and NPS are registered trademarks of Bain & Company, Satmetrix, and Fred Reichheld.